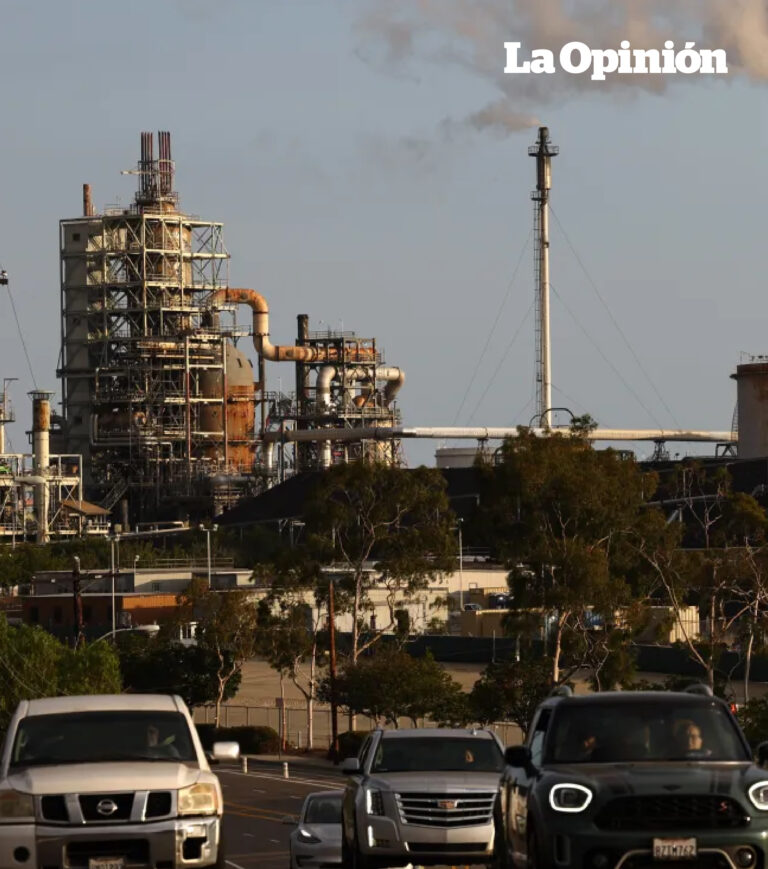

COALINGA, Calif. — In the heart of the San Joaquin Valley, where cattle feedlots and rows of almond and pistachio trees give way to oil fields dotted with creaky old pumpjacks, it’s not hard to find signs of the energy transition. Large-scale solar arrays dot the land where food crops once grew and new electric vehicle chargers are sprouting up next to roads and gas stations.

But the oil industry thinks this area is fertile ground to spread its anti-electrification message and slow down California’s shift to a zero-emission economy.

I visited the area last month because I wanted to understand a Spanish-language ad campaign by the Western States Petroleum Assn. that targets Latinos across California and urges them to speak against policies to move to electric vehicles and equipment.

My tour guide was Argelia León, WSPA’s director of strategic partnerships and Southwest policy, who leads the Levanta Tu Voz campaign. She invited me to hear from the people firsthand in the predominantly Latino rural communities in the heart of the San Joaquin Valley where she was born and grew up.

I’ve spent years reporting in communities like these that are hit hard by air pollution from oil refineries, drilling sites and diesel-choked transportation corridors. Although I wanted to hear the industry’s perspective, I knew I wasn’t walking into a disinterested fact-finding mission, but a calculated influencing operation.

(Tomas Ovalle / For The Times)

Over two days, León, joined for part of the time by a hired PR consultant, drove me around the area for what became an extended debate about the energy transition. I met León’s relatives, childhood friends and other locals during stops at homes, restaurants and a sports bar. When prompted, they offered concerns about moving to EVs and other zero-emission technology. But even the pre-selected assortment of locals was not uniformly resistant to the move toward electrification.

We started our visit in Huron, the 96% Latino farmworker town of 6,000 people where León spent much of her childhood, and soon ran into an uncle of hers outside a mobile home.

“People aren’t ready to rush to all-electric,” she suggested to him, a variation on a refrain she would repeat several times during my visit. He agreed, but also said he relies on an e-bike to get around and uses the town’s ride-sharing fleet of electric cars to get to doctor’s appointments.

(Tony Barboza / Los Angeles Times)

At another stop, José Lopez, a mechanic at Ralph’s Triangle Service, an auto repair shop and smog check, expressed concern about how the community could afford the transition to electric cars. He said many of his customers are farmworkers who share old, beat-up cars and struggle to pull together enough money to pay for oil changes and smog checks.

“But I know the future is electric, for a fact,” he said. “I’m not scared of it, I’m just preparing.”

We stopped by the electric car ride-sharing service run by Huron’s environmental justice advocate mayor, where Teslas and Chevy Bolts were charging and a trailer-mounted, solar and battery-powered shade shelter and cooling station for farmworkers was under construction.

(Tomas Ovalle / For The Times)

When she was tapped to lead the campaign, León said she insisted that “we need to be absolutely transparent. We need to own who we are.”

It was a deliberate choice, León said, to solicit real people to be the messengers instead of using front groups or stock photos.

“I’m a coalition builder, trying to build a bigger coalition in an authentic way so we do not get continuously accused of astroturfing,” she said. “No B.S., that’s why it works.”

(Tomas Ovalle / For The Times)

I found her comments revealing, because they show this industry is still laundering its messages through others’ voices but has learned to deflect some criticism by doing it in the open.

“We’re providing a platform for people to share their story,” she said when I suggested she was taking advantage of our community.

(Tomas Ovalle / For The Times)

After the trip I talked to Cesar Aguirre, who works as air and climate co-director for the Central California Environmental Justice Network and appeared in a debate with León on a local television station over the summer.

He told me that WSPA’s campaign was only a continuation of oil companies’ long history of spreading their money and influence around the San Joaquin Valley. “They’re trying to use Latinos as a token to pressure lawmakers to halt progress for the entire state, instead of using my community as a catalyst and making sure that we are the ones that first receive the electric car chargers,” he said.

The first day of the trip ended with a gathering of friends, family and other locals that León had arranged at a sports bar as a sort of informal focus group.

Some of them have worked in the oil industry and described it as their steppingstone into the middle class. Some complained about declining production and work in the oil fields and blamed state environmental and safety rules. One childhood friend of León’s who has worked in the oil and solar industries told me he has no issues with California shifting to an all-electric economy.

(Tomas Ovalle / For The Times)

Day Two was more visits with relatives and a drive to the oil fields just outside Coalinga. We ended with lunch at a taquería with her cousin, who works for a pump company that serves the oil industry and opposes many of the state’s environmental mandates but told me that even the drilling rigs use pieces of equipment that are powered by solar panels.

By the end of the trip, it was more clear to me than ever that Latinos have a mosaic of opinions and needs but are by no means universally apprehensive about going electric. And it is also clear that our community has much more to gain from a zero-emission economy than it will lose by leaving fossil fuels in the past.

No matter how León and her colleagues at WSPA framed it,this campaign is nothing more than propaganda to delay electrification policies, allowing the fossil fuel industry to profit for as long as possible. It’s reprehensible and we shouldn’t fall for it.